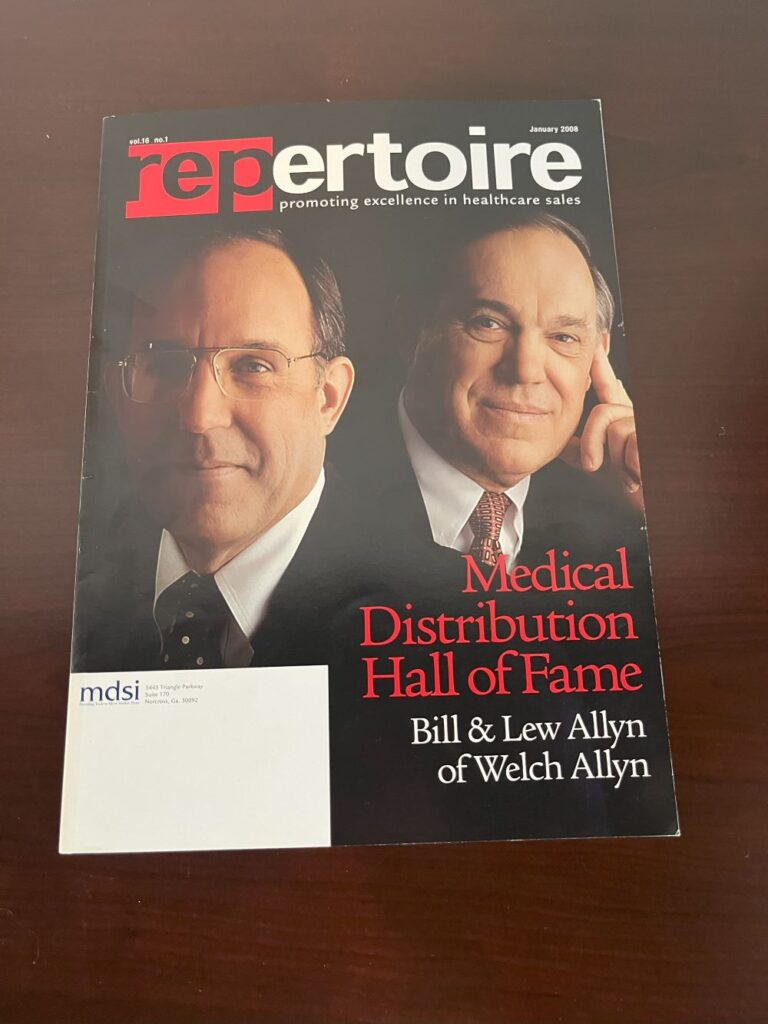

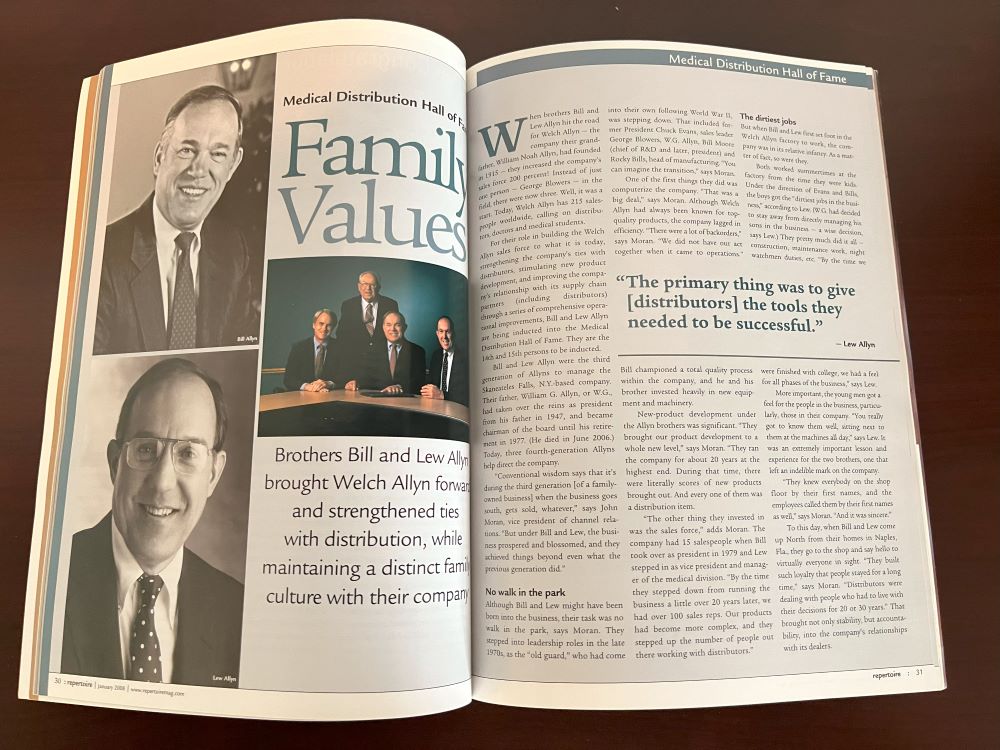

Family Values: Brothers Bill and Lew Allyn brought Welch Allyn forward and strengthened ties with distribution, while maintaining a distinct family culture with their company.

When brothers Bill and Lew Allyn hit the road for Welch Allyn — the company their grandfather, William Noah Allyn, had founded in 1915 — they increased the company’s sales force 200 percent! Instead of just one person — George Blowers — in the field, there were now three. Well, it was a start. Today, Welch Allyn has 215 salespeople worldwide, calling on distributors, doctors and medical students.

For their role in building the Welch Allyn sales force to what it is today, strengthening the company’s ties with distributors, stimulating new product development, and improving the company’s relationship with its supply chain partners (including distributors) through a series of comprehensive operational improvements, Bill and Lew Allyn are being inducted into the Medical Distribution Hall of Fame. They are the 14th and 15th persons to be inducted.

Bill and Lew Allyn were the third generation of Allyns to manage the Skaneateles Falls, N.Y.-based company. Their father, William G. Allyn, or W.G., had taken over the reins as president from his father in 1947, and became chairman of the board until his retirement in 1977. (He died in June 2006.) Today, three fourth-generation Allyns help direct the company.

“Conventional wisdom says that it’s during the third generation [of a family-owned business] when the business goes south, gets sold, whatever,” says John Moran, vice president of channel relations. “But under Bill and Lew, the business prospered and blossomed, and they achieved things beyond even what the previous generation did.”

No walk in the park

Although Bill and Lew might have been born into the business, their task was no walk in the park, says Moran. They stepped into leadership roles in the late 1970s, as the “old guard,” who had come into their own following World War II, was stepping down. That included former President Chuck Evans, sales leader George Blowers, W.G. Allyn, Bill Moore (chief of R&D; and later, president) and Rocky Bills, head of manufacturing. “You can imagine the transition,” says Moran.

One of the first things they did was computerize the company. “That was a big deal,” says Moran. Although Welch Allyn had always been known for top-quality products, the company lagged in efficiency. “There were a lot of backorders,” says Moran. “We did not have our act together when it came to operations.” Bill championed a total quality process within the company, and he and his brother invested heavily in new equipment and machinery.

New-product development under the Allyn brothers was significant. “They brought our product development to a whole new level,” says Moran. “They ran the company for about 20 years at the highest end. During that time, there were literally scores of new products brought out. And every one of them was a distribution item.

“The other thing they invested in was the sales force,” adds Moran. The company had 15 salespeople when Bill took over as president in 1979 and Lew stepped in as vice president and manager of the medical division. “By the time they stepped down from running the business a little over 20 years later, we had over 100 sales reps. Our products had become more complex, and they stepped up the number of people out there working with distributors.”

The dirtiest jobs

But when Bill and Lew first set foot in the Welch Allyn factory to work, the company was in its relative infancy. As a matter of fact, so were they.

Both worked summertimes at the factory from the time they were kids. Under the direction of Evans and Bills, the boys got the “dirtiest jobs in the business,” according to Lew. (W.G. had decided to stay away from directly managing his sons in the business — a wise decision, says Lew.) They pretty much did it all —construction, maintenance work, night watchmen duties, etc. “By the time we were finished with college, we had a feel for all phases of the business,” says Lew.

More important, the young men got a feel for the people in the business, particularly, those in their company. “You really got to know them well, sitting next to them at the machines all day,” says Lew. It was an extremely important lesson and experience for the two brothers, one that left an indelible mark on the company.

“They knew everybody on the shop floor by their first names, and the employees called them by their first names as well,” says Moran. “And it was sincere.”

To this day, when Bill and Lew come up North from their homes in Naples, Fla., they go to the shop and say hello to virtually everyone in sight. “They built such loyalty that people stayed for a long time,” says Moran. “Distributors were dealing with people who had to live with their decisions for 20 or 30 years.” That brought not only stability, but accountability, into the company’s relationships with its dealers.

Product designer

By their own admission (and observations from others, including W.G., in his 1996 book, “An American Success Story”), Bill and Lew brought unique strengths to the business. If Lew had the design sense, Bill had the engineering sense.

Lew Allyn attended the college of fine arts at Syracuse University, majoring in industrial design. “Industrial design involves first of all understanding what the customer needs, what his problems are, and all the human factors of the product,” he says. “Then you do the design work — how the product will handle and fit in someone’s hand, its eye appeal, its aesthetics. What you’re doing is bridging [the gap] between the engineer — who’s directing the technical [aspect] of the product — and the end user.

“You can have two products that do essentially the same thing. But the one that looks right and feels right is the one that will be successful. It has a lot to do with the customer’s perception of the product and their loyalty to it.”

Lew saw his interest and talent in the design side of medical products as an opportunity to contribute something to the company, he says. One thing that he worked on diligently throughout his career at Welch Allyn was developing and maintaining a “family look” to the company’s stable of products. “When the doctor looks at a new product, what you like to hear him say is, ‘That looks like a Welch Allyn product,’” he says. “It has to do with the color, form, shape, feel and size.”

Lew’s years on the road under the tutelage of George Blowers taught him another valuable lesson. “[Blowers and Evans] were really students of product knowledge, that is, knowing their products inside and out,” he says. “Chuck had been a school teacher, and he believed in teaching. He believed that you had to educate yourself first, then your customers, so you can give them the tools they need to go out and sell your products.

“George felt we were competing for our distributors’ time. The more confident the distributor was in our product, the more likely they were to talk to their customers about it.

“The primary thing was to give [distributors] the tools they needed to be successful,” he says. “There was a lot of new-product introduction.” In addition to calling on distributors, the Welch Allyn team tried to work any medical schools in the area, always bringing the local distributor along. “We’d do the presentations, but the distributors would do the follow-up work,” he says. “And we’d also work with end users, tying in the local distributor too.

“George [Blowers] and John [Moran] were unique in that they looked at the relationship between Welch Allyn and the distributors as one that had to be a win-win,” he continues. “It had to be balanced. If it was going to be good for Welch Allyn, it had to be good for the dealer. And they had a very good sense for what was needed out in the field.

“Back when I started, so much was based on relationships. [Business] was very relationship-oriented. I think that probably has changed somewhat over the years. But in our industry — and maybe our industry is unique — relationships are still very strong. And I think that’s terrific.”

Lew was to carry those relationship-building skills overseas, as he developed the company’s international business, first in Europe, then Latin America and Asia. Today, its overseas business accounts for somewhere between 35 and 40 percent of the company’s business.

The engineer

But good relationships alone couldn’t carry the company into the future. A strong R&D; program and operational improvements were crucial. Bill Allyn was instrumental in both.

Bill graduated with an engineering degree from Dartmouth. He also received a master’s degree in business administration. After spending some time in the Coast Guard (something Lew did as well), he joined the company, first in the field as a salesman. His territory was big, as it had to be — extending from New England to Ohio to Kentucky to Washington.

“I had been in the field for about four or five years when a strange thing happened,” he recalls. Welch Allyn had developed the first mass-produced fiber optic product for its otoscope. Through what he describes as an incredible stroke of luck, one of the company’s engineers happened to live next door to someone who called on IBM. The big computer company was

having trouble with its fiber optic products. That was a big problem for Big Blue, which needed a reliable fiber optic light source to read its punch cards. So Bill visited IBM in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and came back with a very large order. “My dad said, ‘Bill, maybe you should think about starting a new division of the company — an industrial division,’” he recalls. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

It was to be the first of the company’s successful non-medical ventures. Originally called the industrial division of Welch Allyn, the division began manufacturing fiber optics, light bulbs and later, bar-coding equipment. The business eventually became Hand Held Products, which the company later spun off. (In October 2007, Minneapolis-based Honeywell announced its intention to acquire Hand Held Products, for approximately $390 million.)

Bill and Lew spun off another of the company’s technologies — used in its colonoscopes — when they recognized that the technology was transferable to other industries. The aircraft industry needed scopes to examine turbine blades and jet engines, and the nuclear industry needed them to check for potentially disastrous cracks in reactors. “We called the business Everest Imaging,” recalls Bill. “The reason we chose that name was because our biggest competitor was Olympus. We wanted to be bigger than Mt. Olympus, so we became Everest.” (The company was ultimately purchased by General Electric and is now part of that company’s Inspection Technologies business.)

Eye-opener

In 1985, Bill had another experience that was to shape the future of the company and its relationship with its distributors. “A lot of people knock on our door wanting to buy us,” he says. In the mid 1980s, one of those suitors was Hillenbrand Industries, the Batesville, Ind.-based medical equipment manufacturer. Bill told Hillenbrand executives that Welch Allyn wasn’t for sale, but he nevertheless received an invitation to travel to Batesville to check out Hillenbrand’s manufacturing facility. “It was the first time I had seen a formal quality program and just-in-time manufacturing,” he says. The operation was in marked contrast to how Welch Allyn operated.

“They had really simplified their [manufacturing] system,” he recalls. Although Hillenbrand was heavily computerized, the company had painted yellow squares on the shop floor. No worker on the line should have more parts on hand than could fill each square. The idea was to “thin out” its manufacturing operation, reducing the number of raw materials as well as finished goods in the plant. It worked.

“Before, they had had a system like ours,” recalls Bill. “You’d make a six-month or year’s supply of a part, then put it in the warehouse. But that’s dumb, because some engineer might change the design; then all those parts become obsolete. And then there’s the cost of all that inventory just sitting there.

“We went through [the Hillenbrand] factory, and there were all these empty rooms, where they used to have six months’ supply of products. Now, they were making just exactly what they needed for the next day. It was the first time I had seen this, and it was dramatic.” Upon his return to Skaneateles Falls, Bill began transforming the way Welch Allyn manufactured products.

TQM

Not only was implementing just-in-time manufacturing on his agenda, so too was the closely related concept of total quality management. “Before this, if we needed a hundred parts, we’d make 130 and look for the hundred good ones,” recalls Bill. In TQM, the point is to make a hundred parts and expect every one to be good, he explains. “It’s a better approach, because first, you can’t afford to pay for the old process, with so many people looking for defects; and second, you can’t afford to make all those faulty components.

“It took a terrific amount of education” to implement TQM. Managers visited other plants, and many Welch Allyn employees attended the Crosby School of Quality in Winter Park, Fla., founded by quality guru Philip Crosby. As part of its training, Welch Allyn created a fictitious company, Aunt Jane’s Cookie Factory, so that employees could test out TQM concepts in theory before implementing them on Welch Allyn’s shop floor.

At the same time, the company retired its old machines and replaced them with computer-driven ones, which were capable of creating parts by themselves, rather than passing them from one machine to the next in order to create a part. “This made just-in-time work,” says Bill. “And just-in-time went along with quality, because there’s no sense in a just-in-time system that uses the wrong parts. When people saw this, they said, ‘Yeah, now we see what you’re talking about.’”

The end result of all the changes was a shorter manufacturing cycle and, according to Bill, better service to distributors. “Distributors want what they can sell tomorrow,” he says. “It’s not unusual for the dealer to sell a product and order [a replacement] today, and for us to ship it out tomorrow. So the shipping cycles have to be much shorter.”

Commenting on all the operational changes, Lew Allyn says, “Prior to all this, we’d sit around at the end of the year, pull out the crystal ball and forecast what our customers would buy in the following year. But sometimes we were way off. So you’d have a buildup of raw materials and finished parts…[because] the customer really wanted something else. We had incredible delivery problems, materials problems, problems with manufacturers of raw materials. And changing the size or formula [of our products] brought us to our knees; it could throw us off for months. What we wanted to do was move away from the mode of building inventory and putting it on the shelf and hoping that’s what the customer wanted.

“We went to our suppliers and said, ‘We won’t push you so much on price, but we want you to be the supplier of this product, and we want to make sure you [are able] to ship us that product when we need it. And it has to be right 100 percent of the time.’”

By implementing TQM and just-in-time, Welch Allyn’s delivery rates “went way up,” says Lew. “Overall, I don’t know if we could have survived had we not done these things. I don’t think we could have.”

New product development

Under the direction of medical R&D; Manager Rich Newman (who picked up the R&D; reins from Bill Moore when the latter became president of the company in 1977), Welch Allyn stepped up its new-product-development process. “We felt we had to develop new products, so we spent a lot of time and resources on R&D;,” says Lew.

Bill agrees that it was essential for the company to do so. “When you visit a medical distributor, the first thing people will ask you is, ‘What’s new?’” he says. “If you have the same old thing you’ve had for 30 years, [they’re not interested.] But if you have something new, some new product to make the hospital and doctor’s life better — and that the distributor can make some money on too — that’s a very important part of our business.”

Distributors noticed the changes. “I recall about the late 1960s, when I heard that Bausch & Lomb had offered to buy out [Welch Allyn],” says Berk Biddle, former president and principal shareholder of Biddle & Crowther Co., Seattle, Wa. (which was sold in 1995 to Bergen Brunswig, now Cardinal Health). “I only visited the factory once in Skaneateles, and was very impressed with how advanced and productive they had become. They had switched over to producing products to order, rather than the typical buildup of inventory for storage, which other manufacturers were doing. Lew showed me a new device … that could take a designer’s ideas and make a prototype from his plans on the spot.”

Company culture

Like others, Biddle notes how personable the company was, and remains. “I recall Lew picking me up from the hotel in the morning, and we went to a little café in Skaneateles for breakfast,” says Biddle, recalling a trip to Upstate New York. He also recalls having dinner with the Allyns in Naples. “On the way, one of the Allyns picked us up in their station wagon and stopped for gas. He got out and pumped his own gas …. I only wish more companies had people who owned them and operated them in such a fine fashion.”

Yates Farris, vice president, primary care markets, IMCO, Daytona Beach, Fla., and formerly with Winchester Surgical in Charlotte, N.C., has some memories of his own. “As an example of the relationship-building attitude of [Bill and Lew], I recall a trip to Skaneateles back when I was the sales manager at Winchester Surgical. David Allyn, Bill’s son, was the Welch Allyn sales rep for the Carolinas. As contest winners, six of the Winchester sales reps and myself accompanied David for a long weekend to Welch Allyn for business and fun time, coupled with the factory tour, etc. One would think Welch Allyn would put a bunch of guys like this in a motel ‘way down the road.’ Instead Bill and his wife, Penny, moved out to their cabin on the lake and gave us their house to use for the weekend. That certainly took lots of nerve.

“Even today, whenever IMCO has groups up to Welch Allyn, Bill and Lew are always around conducting factory tours, having lunches and dinners with the ‘troops,’ and just making everyone feel welcome and at home. These sales reps always leave with even a greater feel of dealing with a company that truly cares.

“Bill and Lew have exemplified themselves in continuing a ‘family culture,’” says Farris. “If I had to say just one thing about them, it would be that during their regime, Welch Allyn experienced terrific growth with lots of obstacles, and up and down economies. But they both maintained and handed down that ‘family culture’ that still defines their company.”

This article originally appeared in the January 2008 issue of Repertoire Magazine.