Sepsis disguises itself too well

Sepsis: It’s subtle, and deadly. It offers some clues of its existence, but you have to be watching for them. Early diagnosis is essential to stop it in its tracks.

Sepsis: It’s subtle, and deadly. It offers some clues of its existence, but you have to be watching for them. Early diagnosis is essential to stop it in its tracks.

Sepsis impacts between 900,000 and 3 million people in the United States each year, according to Terri Lee Roberts, BSN, RN, CIC, FAPIC, senior infection preventionist for the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority, who has written and spoken extensively about the subject. Over a two-year period (April 2014 – March 2016), 486 potential occurrences of sepsis with 17 potential sepsis-related fatalities were recorded for residents in long-term care in Pennsylvania, she says.

With a mortality rate of 15 percent to 30 percent, it is a leading cause of death in the United States. Adults age 65 years or older are five-fold more likely to have sepsis than younger adults (6.5 percent vs. 1.3 percent), and nursing home residents are seven-fold more likely to have sepsis, compared with sepsis rates in adults not residing in a nursing home (14 percent vs. 1.9 percent). Eighty percent of sepsis cases occur outside of the hospital.

“Over 70 percent of patients who present with sepsis will recover if treatment is initiated on a timely basis and pursued aggressively,” says lab expert Jim Poggi, principal, Tested Insights, Providence Forge, Virginia. “The key is early diagnosis and initiation of treatment, typically with broad spectrum antibiotics and fluid replacement therapy.”

But oftentimes, early identification and treatment fail to occur.

“The signs of both infection and organ dysfunction may be subtle and difficult to recognize in older adults with multiple comorbidities,” says Roberts. “Fever may be absent. There is a lower incidence of tachycardia and hypoxemia. Confusion, delirium, weakness, falls, anorexia, and incontinence may be symptoms of sepsis, but they can be non-specific in older adults.”

What’s more, in long-term-care facilities, it’s often a certified nursing assistant (CNA) – not a professional nurse – who is at the bedside with the resident, and the CNA may not recognize these subtle changes in a resident’s medical condition as an early sign of sepsis, she adds.

What it isn’t … and what it is

“First of all, a couple of things sepsis is NOT,” says Poggi. “It is NOT a disease and it is not contagious. While its onset is a complication of an infection, sepsis is the body’s overwhelming and life-threatening response to the infection.”

While any infection can lead to that life-threatening response, some have a higher association with sepsis, says Poggi:

- Respiratory infections including pneumonia, group A streptococcus and influenza.

- Urinary tract infections.

- Enteric (GI) diseases, including difficile.

- Skin infections, including MRSA.

- Blood stream infections (bacteremia).

In 2016, the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock defined sepsis as the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in addition to a documented or presumed infection, continues Poggi. SIRS symptoms include:

- Fever of more than 38°C (100.4°F) or less than 36°C (96.8°F).

- Heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute.

- Respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute or arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2 ) of less than 32 mm Hg.

- Abnormal white blood cell count (>12,000/µL or < 4,000/µL or >10% immature [band] forms).

The Sepsis Alliance – a nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness of sepsis – uses an acronym to define typical patient conditions that can lead to a presumptive diagnosis of sepsis:

- S: Shivering, fever or very cold.

- E: Extreme pain or discomfort.

- P: Pale or discolored skin.

- S: Sleepy, difficult to rouse, confused.

- I: “I feel like I might die.”

- S: Shortness of breath.

Diagnosis

On the laboratory front, sensitivity, specificity and speed of available tests have presented challenges, says Poggi. CBC tests, including elevated WBC and decreased platelets, are sensitive but non-specific. The same is true of lactate and C-reactive protein. While microbiological cultures can identify specific organisms, routine plated media methods have lacked the speed needed to support a rapid diagnosis.

Lab diagnostic tools include:

- Blood, wound or urine culture.

- Molecular testing for specific pathogens.

- Complete blood count with differential.

- Serum lactate.

- Metabolic and organ panels, including Basic Metabolic panel, AST, ALT, creatinine and urea nitrogen.

“Recent advances in molecular assays that can diagnose a variety of pathogens within hours have substantially improved speed of result for bacterial identification,” says Poggi.

Procalcitonin is a newer assay that is highly correlated to sepsis as well as its progression, he continues. Procalcitonin concentration is < 0.15 ng/ml in normal patients, but quickly rises in concentration with severity of the disease process (0.15-2.0 ng/ml for mild bacterial infections and > 2.0 ng./ml for sepsis). In addition, the procalcitonin test can be performed within hours rather than days.

In the public eye

Awareness of sepsis among the public is higher than ever, but there is more work to be done, says Roberts.

Awareness of sepsis among the public is higher than ever, but there is more work to be done, says Roberts.

A 2012 incident involving a 12-year-old boy in New York drew national attention to sepsis.

On March 28, 2012, the boy, Rory Staunton, scraped his arm diving for a ball in gym class. No one recognized the early signs of sepsis and he was misdiagnosed with dehydration. By the time he was diagnosed with sepsis, it was too late, and Rory died on April 1. His death was a springboard for a discussion about the seriousness of sepsis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched a comprehensive campaign targeting clinicians and the public on how to prevent sepsis, how to identify risk factors, how to recognize warning signs, and why medical attention should be sought immediately, as sepsis is a medical emergency. The CDC wanted people to ask the question, “Could this be sepsis?” says Roberts.

“Sepsis Alliance has done a great job of raising awareness that people who were otherwise healthy have succumbed to this syndrome,” says Roberts, who has had personal experience with sepsis. About 10 years ago, her 10-year-old nephew almost died from sepsis after developing an infection from a splinter of mulch under his fingernail. Several days passed before the infection – and resulting sepsis – was finally identified, and he is healthy today.

Screening for sepsis

Although anyone can get an infection, and any infection can lead to sepsis, some people are at higher risk of infection and sepsis, says Roberts. They include:

- Adults 65 or older and children less than 1.

- People with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, lung disease, cancer, andkidney disease.

- People with weakened immune systems, such as those who have had a solid organ transplant, people who are on long-term steroid therapy or taking chemotherapy. Additionally, immune function decreases with age.

Because of the difficulty in identifying sepsis, a long-term-care-specific sepsis screening tool may help to optimize safety in this population, she says. INTERACT’s “Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool” or the Minnesota Hospital Association’s LTC-specific “Seeing Sepsis Tool Kit” to facilitate early detection of sepsis are available for healthcare providers to use. “I am often called upon to provide education regarding the early detection of sepsis in all healthcare facility types, whether it be through professional conferences, statewide/multistatewide webinars, or in-person presentations,” she adds.

Judicious use of an electronic health record can help.

“The EHR has the strong potential to improve the detection of sepsis early by collecting and organizing the clinical data required to make the diagnosis,” says Roberts.

More specifically, a facility’s EHR system could collect vital signs and laboratory test information on patients, triggering a “sepsis alert” for those with the facility’s defined parameters, such as =2 SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) criteria (fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis) plus =1 major organ dysfunction (SBP = 90 mm Hg, lactic acid =2.0 mg/dL).

“A facility could incorporate their chosen sepsis screening tool into their EHR system, and a positive screening could trigger a ‘sepsis alert,’” she adds.

SUHEAD: Communication

Screening and early detection are just the beginning. Without good communication among the long-term-care team, little action may result.

“Because the sepsis syndrome is comprised of a constellation of signs and symptoms, and because no one test can identify sepsis, the healthcare team must communicate effectively and timely to recognize the signs of early sepsis and implement evidence-based therapies to improve outcomes and decrease mortality,” says Roberts.

“Healthcare providers – not just LTC team members – may have different communication styles. Differences in training, cultural differences, culture barriers, etc., may lead to lack of communication, miscommunication, or ineffective communication.” Exacerbating the situation are high turnover rates among CNAs, decreased continuity of care, and the fact that many clinicians are not onsite to be able to communicate with the rest of the healthcare team directly.

“It’s the team members who spend the most time with the resident – not just licensed professionals – who can best recognize subtle changes in a resident’s condition,” she says.

“When I worked in a facility as an infection preventionist, I made everyone my front-line ‘infection prevention eyes.’ “I would tell them, ‘If you see something you don’t think is right, tell someone.”

She recalls a situation where an environmental services staff member recognized that one patient – a 16-year-old boy – was acting differently. Over about 12 hours, the patient had lost his interest in video games and didn’t want to talk, as he had before. It turns out the boy had indeed developed sepsis. But he was treated in time to save his life.

“Everyone plays a role.”

Editor’s note: INTERACT® (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers) is a quality improvement program from Pathway Health (www.pathway-interact.com) that focuses on the management of acute change in resident condition. It includes clinical and educational tools and strategies for use in every day practice in long-term care facilities.

——————————————————————-

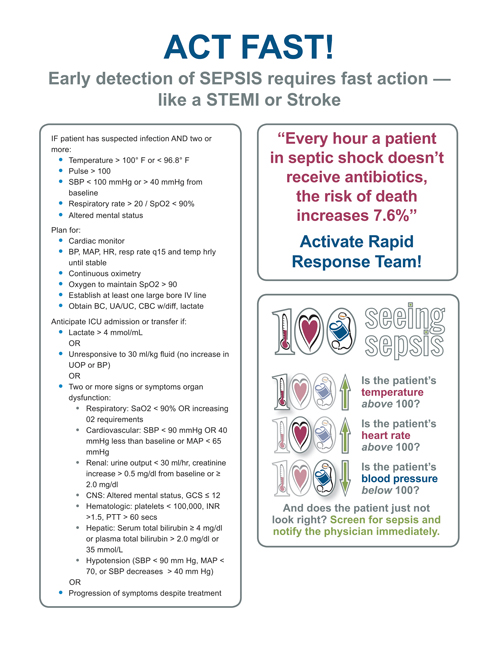

Graphic:

We have permission to run the ACT FAST graphic at this URL: https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/sepsis%20tool%20kit/9_Seeing%20Sepsis%20Act%20Fast%20Poster.pdf

We need to include this: Reprinted permission of the Minnesota Hospital Association

Sepsis: After the hospital stay

Sepsis is the leading cause of death of hospital patients, and half of survivors do not completely recover, with a third of those dying in the following year and a sixth experiencing severe, persistent physical disabilities or cognitive impairment. In one study, only 43 percent of previously employed patients returned to work within a year of contracting septic shock and only 33 percent of patients living at home prior to contracting sepsis returned to living independently by six months following their discharge.

University of Pittsburgh and University of Michigan medical scientists studied the issue and developed recommendations for post-hospital recovery care.

“We need to focus not only on saving the patient’s life, but on ensuring the patient will have the best possible quality of life after leaving the hospital,” said Derek Angus, M.D., M.P.H., chair of University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Critical Care Medicine, and an author of a recent article about sepsis in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Angus and lead author Hallie Prescott, M.D., M.Sc., assistant professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine in University of Michigan’s Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation, recommend three strategies to prevent long-term disabilities:

- High-quality early sepsis care that includes rapidly following protocols to help the patient fight infection, managing pain through light sedation that allows for the patient to be awakened and reoriented daily, and encouraging early mobility while the patient is still hospitalized.

- Post-discharge assessment and treatment that gets patients into rehabilitation with physical, occupational and speech therapy shortly after discharge, and quick referral to therapists if new impairments develop.

- Screening of patients for conditions that may have been present prior to hospitalization, such as high blood pressure, and tailoring post-discharge medications to account for individual patients’ increased susceptibility to new complications.

Rory Staunton’s story

The parents of 12-year-old Rory Staunton have done much to raise the public’s awareness of sepsis. They tell his story on the website of the Rory Staunton Foundation for Sepsis Prevention.

“In March 2012, our son Rory was a strong, 5-foot-9-inch, 169-pound, 12-year-old boy, living a life full of laughter and love. … On Wednesday March 28, 2012, Rory dived for a ball during gym class at the Garden School in Jackson Heights, NY, and cut his arm. The gym teacher did not send him to the nurse, who was on duty in her office, but instead applied two band-aids. He did not clean Rory’s wound. After midnight Rory woke up moaning with a pain in his leg. We coaxed him back to sleep and the following morning he had a fever of 104.”

The pediatrician diagnosed a stomach virus that had been making its way around New York.

“She advised us to take him to the hospital for re-hydration and fluids, she said he would have diarrhea the next day and the virus would run its course. Dr. Levitsky assured us there was ‘nothing to worry about.’

“We made our way to the ER department at a major New York medical institution, where the doctors said Rory’s discomfort was caused by a sick stomach and dehydration. They gave him two bags of intravenous fluids. Three vials of blood were drawn and he was given a prescription for an anti-nausea drug called Zofran.

“The pediatrician at the hospital who examined Rory wrote ‘pt improved’ on his chart before discharge. She said it was a stomach virus and that Rory could take up to a week to recover.

“We brought Rory home on that Thursday night; he fell into a deep sleep but the following morning Friday, he continued to complain of pain. We repeatedly called his pediatrician … and told her Rory wasn’t eating and we couldn’t control his temperature with Tylenol or Motrin. We brought Rory back to hospital on Friday evening and this time they admitted him to the ICU. He was gravely ill.

“Rory was fighting a serious infection. This infection had been in his blood when we brought him to his pediatrician and to the hospital on Thursday. Bacteria had entered his blood, through the cut on his arm. Rory was in septic shock.

“When we brought Rory to his pediatrician and the emergency room on Thursday night, he was in fact fighting for his life. Critical information gathered by his pediatrician and at the hospital that night had not been viewed as important. In fact, Rory’s vital signs had worsened before he left the emergency room on Thursday night.

“The blood values that the doctor ordered stat (immediate) were not viewed by the hospital doctor who ordered them. The laboratory in the hospital had flagged Rory’s blood as showing an abnormality within an hour of Rory’s arrival there, but there was no system in place and no one took the time to alert the emergency room with this information. When the critical value tests returned showing Rory was extremely ill, we had already left the hospital.

“The hospital made no attempt to follow up with us, his family, to inform us that he was seriously ill. Our pediatrician did not follow up with the hospital on Friday when we called her with our concerns that he was not improving.

“Rory fought valiantly to survive throughout Friday and Saturday but it was too late. On Sunday evening, Rory died.”